The dynamics of the present moment have a terminal meaning for people like this writer, who may not live to see the general elections of 2024.

The ongoing campaigning for the next assembly elections are clearly the most important in this regard. Without a doubt, the results will reveal a lot about how the country will shape up in the next years, particularly in Uttar Pradesh.

However, the return of debate to the Houses of Parliament on the formal “motion of thanks” to the President for his address has hinted at ideological concerns and orientations that appear to represent a change from the miserable stasis and pessimism of previous years.

During that debate, speakers from the Congress, the All India Trinamool Congress, the Rashtriya Janata Dal, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, the Samajwadi Party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, and even the Biju Janata Dal and Telangana Rashtra Samithi, unravele

The crony-complicit nature of its economic “performance,” its role in causing irreparable damage to the social fabric of the nation’s composite life, the credibility of state institutions, and the impartiality of prosecutorial law-enforcement systems were all sharply criticised without any pusillanimous dithering.

Listening to these talks provided reassurance that democratic vigour and the critical spirit founded in the hard work of grassroots knowledge, indisputable research, and adherence to constitutional injunctions are still alive and well.

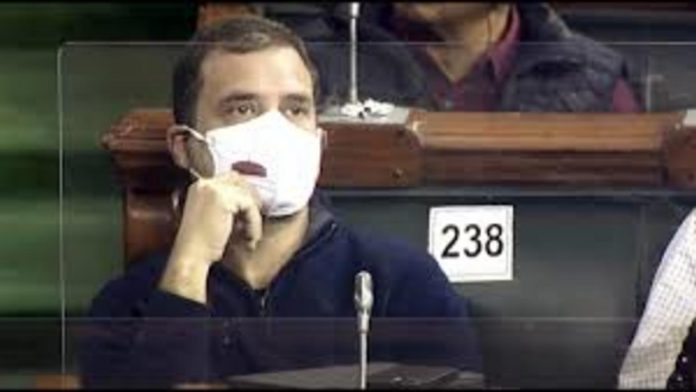

If Rahul Gandhi’s speech had the stamp of a watershed moment, it was because it came from the de facto leader of the alternative national political formation, whose own record had previously been blemished in areas that Rahul Gandhi criticised, and which, however the ruling right-wing may downplay it, continues to be seen as its main likely nemesis.

His calm demeanour made it evident from the time he stood up to speak that he had something significant to say.

And he spoke critical things about the nation’s economic, political, and cultural status – all with a sharpness of articulation and emphasis that required many hours of reading and corrective thought.

Rahul Gandhi’s persuasive encapsulation of the economic ideology of the current right-wing government took in the major axes of its macro-economic preferences, such as have today rendered India perhaps the most brutally unequal of societies worldwide, in keeping with what he has sought to share with the citizenry over the last few years.

Rahul Gandhi supplied indices that corroborated his concept that there are now two obviously distinct Indias, a nod to Benjamin Disraeli (who first noted how the England of his time was ‘two nations, the rich and the impoverished’).

At one end, he proposed an India in which 98 individuals have assets equal to those of 55 crore other Indians, and where 142 billionaires (up from 140 a year ago, the world’s third highest number of billionaires) have increased their wealth from Rs 23 lakh crores to Rs 56 lakh crores during the Modi administration, and at the other end, an India that ranked 101 in the Global Hunger Index, below all of India’s minion neighbours, including the reviled DR Congo.

He might have gone on to say that India has the world’s greatest population of malnourished and stunted children, and that this great nation, on its way to becoming a $5 trillion economy, spends the smallest percentage of its GDP on education and public health.

Rahul established how this unconscionable state of the nation’s economic life has resulted not only from a wholesale transfer of wealth from public holdings to private hands, but also from a small group of people, primarily two favoured cronies, reading off two discrete lists of assets and holdings, even as he made it clear that the Congress was not a blanket enemy of the nation’s corporate sector.

This was the easy part, because the vast and callous capture of wealth over the last seven years has become common knowledge, despite the lauded direct benefit programmes, most of which are phoney and have no actual impact on the impoverished lives of approximately 80% of Indians.

The irony is that the regime’s lofty claims here are at odds with the fact that it has been forced to provide free basic rations (mostly cereals) to this large mass of people whom it claims to have raised into economic respectability in the same breath.

The fact that prohibitive prices for oils, fruits, and vegetables prevent this large group of people from even considering nutrition is, of course, a not-so-hidden and horrible truth.

It remains to be seen what measures a Congress-led government would pursue in the future to combat the wild and bloodthirsty capitalism that has evolved from the neoliberal economic policies instituted by a Congress-led government in 1991.

It is evident that tokenist welfarism may no longer be sufficient to restore equitable sanity to national wealth management and distribution, and that certain far-reaching structural adjustments may be required.

It was here that Rahul Gandhi articulated a fresh and unexpected structure of perceptions and convictions that will be the topic of renewed research and debate about the politics of a new possible collective future.

He was obviously following a course that arose from a careful examination of how the state intended to be turned from a democracy to one ruled by a “king, a shahenshah, a ruler of rulers,” a goal that the liberation movement had battled and rejected in 1947.

Nothing offends the principle of federalism more than the prime minister’s sickeningly repetitive reference to the importance of “double engine” governments; this assertion clearly implies that the ruler may be expected to shower bounties only on those states that elect his party to power – a stipulation that is deeply offensive both to the democratic structure and to constitutional principles. Despite this, no segment of the media seemed to wish to make even the tiniest comment on the “double engine” thesis’s proliferation.

What was remarkable about Rahul Gandhi’s presentation here was the understanding he offered of how the right-wing had a view of India that was completely out of sync with the bouquet-like variety of the country’s discrete linguistic, cultural, self-respecting plurality over millenia of living, and how the unique and unparalleled diversity of this land’s people had achieved an organic unity rooted in a rich skein of negotiations, conversations, and mutually beneficial relationships over thousands of years.

When it came to history, Rahul Gandhi emphasised that no empire had ever succeeded in homogenising this rich and diversified plurality, and that whenever they tried, they were met with strong counter-hegemonies founded on the genius of deeply rich and self-respecting identities.

As Trinamool Congress leader Jawhar Sircar pointed out, India has never had “central rule” for more than about five centuries of its five-millennia-long history — the Mauryas for 200 years, the Mughals for 120 years, and the British for another 150.

As a result, Rahul Gandhi said that the assumption of a centralised dictatorship ruled by a “ruler of rulers” was diametrically opposed to the genius of India’s diversified history and polity, and would inevitably provoke reactions that would jeopardise the country’s peace and harmony.

Rahul Gandhi laid a firm ideological foundation for his belief that only a negotiated cooperative federalism could hope to both keep the republic together and meet the ends of the democratic and egalitarian ideals enshrined in the constitution by pointing out that the constitution defined India as a “union of states” rather than a homogeneous “nation.”

Political experts have pointed out that the Congress carries a large part of the blame for debilitating federalism in the way Rahul Gandhi outlined in his watershed speech, beginning with the expulsion of Kerala’s first ever elected communist government in 1959.

This is undeniable. And, given the firmness with which he has now formulated his understanding of India’s diversely rich and intertwined social and cultural history, Rahul Gandhi’s offering would have been doubly persuasive if he had acknowledged that reality, though it does appear that given the firmness with which he has now formulated his understanding of India’s diversely rich and intertwined social and cultural history, he will not hesitate to do so at some point in the future. It is naturally difficult for him to simply state that he had no role in his party’s prior excesses, despite the fact that no fair-minded assessment of India’s post-independence existence can fairly equate the scope or frequency of those excesses to what we have witnessed over the last seven years.

We must recall that, with the exception of the 19-month Emergency, state authorities and socially empowered satraps have never been used as effectively to undermine constitutional rule as they have been throughout the Modi regime’s tenure. Neither was the country’s largest minority cruelly demoted and discouraged as they have been since 2014.

His admonition is clear: no central power can ever aspire to conquer broad swaths of India, whether in the south, east, or the suppressed area of Jammu and Kashmir. This is a likely trajectory for the great old party in the months and years ahead, with a focus on forming alliances with other groups rather than imposing hegemony from Delhi, or even just from the prime minister’s office.

Clearly, the thrust of Rahul Gandhi’s stated ideological vision here poses a challenge to the Hindutva right-“demonic” wing’s hegemonisation, (as his seminal departure from some previously disabling thinking within the Congress may be set to be jettisoned), preparing the party for a sentient equation with regional forces that have hitherto tended to view the grand old party as yet another oppressive behemoth), preparing the party for a sentient

It should be obvious that this decision could have significant repercussions for the next general election. One could guess that secular parties other than the Congress have taken careful note of everything Rahul Gandhi has said, and may take steps that were previously unthinkable.

Of course, how the grand old party’s reorganisation proceeds in the coming months remains to be seen.

Rahul Gandhi brought home the more unsavoury sides of a centralising cultural mindset by recounting a tale from his conversation with some political leaders from Manipur.

He described how these Manipur leaders were offended when they were ordered to remove their shoes before entering a chamber to meet the home minister, only to learn that the minister was wearing his chappals while they were barefoot.

In a rather gauche Brahminical assertion, Rahul Gandhi reaffirmed his earlier democratic concern about overbearingly centralised political authority by suggesting how that autocratic bent of mind extended to enforcing degrading inequalities in cultural practise at the highest levels of political life, and how this amounted to putting “lesser” Indians in their place.

This reminded me of King George’s request that Gandhi dress “properly” for his audience with the king during the Round Table conference – a request that Gandhi famously refused.

It is hoped that such rejections would increase in the coming days at all levels of national life, by men and women, Hindus and Muslims, leading to a societal uprising against majoritarian decrees about what we may or may not eat, wear, think, or believe.

The sum and substance of Rahul Gandhi’s speech promotes the belief that the Hindutva forces’ now brazenly and coercively overt and proclaimed goal of declaring India a Hindu Rashtra, with all the cultural connotations that entails, will never find acceptance in three-quarters of the country.

And the current electoral campaigns appear to indicate that the ruses used by a relentlessly anti-poor dictatorship in relation to communal and sectarian shenanigans may have run their course.

Meanwhile, if Rahul Gandhi has indeed restructured the grand old party’s political and cultural perceptions and relationships, including a more forthright abandonment of the temptation to ape cultural majoritarianism in favour of secular platforms of praxis, the country may have been given a choice it has lacked for the past decade or so.