Working with a script written by a group of six writers, showrunner and filmmaker Nikkhil Advani brings the gruelling last phase of India’s freedom movement to the screen in Freedom of Midnight by fusing elements of fantasy and imagination with strong historical accuracy.

The drama series on SonyLIV, which is produced by StudioNext and Emmay Entertainment, is meticulously designed. It combines grandeur and intimacy, accuracy and persistent solemnity, and a keen understanding of the eternal contemporaneity of political decisions with far-reaching effects made by the architects of a free nation forged in fire during a time of immense upheavals.

Although the main storyline of Freedom at Midnight only covers two years and ends with the uncertain future that a newly independent India stares at amid the Partition riots, the work is huge and primarily based on the 1975 book of the same name by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre.

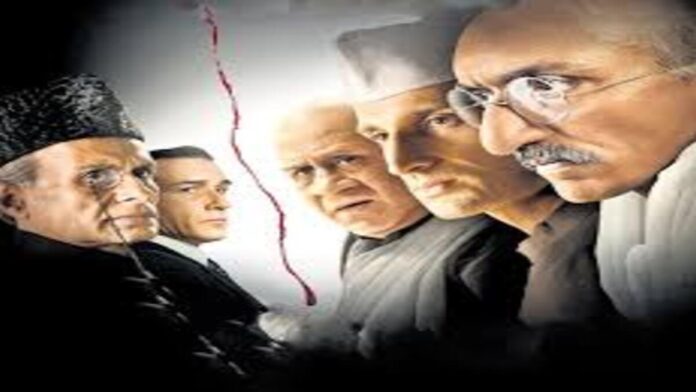

Despite having hundreds of actors, Freedom at Midnight focusses on a few men and a woman or two who spearheaded the difficult and drawn-out process of negotiating the transfer of power, which was unavoidably full of conflict and back and forth.

Advani has come a long way as a filmmaker and storyteller since the re-release of his 2003 directorial debut, Kal Ho Naa Ho. His Rocket Boys imbues Freedom at Midnight with the gravitas that it demands.

The director’s artistic decisions are excellent. His available performers are ideally suited to the project’s requirements. Additionally, the show’s technical qualities are all excellent. When they work together, they not only make sure that the serious topic remains front and centre, but they also make sure that the effort is not overburdened.

You will find it difficult to criticise the points of emphasis and the lines of argument that Advani’s interpretation of events employs, regardless of your political inclinations and the extent to which WhatsApp forwards have influenced your historical knowledge. This is because Advani’s interpretation is evidently based on extensive research and a book that, with a few exceptions, got everything right.

If there is anything that is amiss in Freedom at Midnight, it is the fact that each of the key dramatic personae is put into an airtight ideological block that represents a specific line of thinking that is played off against the swirling forces of history for the purpose of generating drama and conflict.

Jinnah is an unwavering supporter of a separate country for Muslims, Gandhi is the wise man, Nehru is an idealist dedicated to the concept of a united India, and Patel is a pragmatic who thinks it is OK to amputate a hand in order to preserve an arm. There isn’t much room in the show for these extraordinary men to fall victim to human inconsistencies.

Instead of A-list celebrities, Freedom at Midnight is fuelled by performers who boldly and meticulously bring the aforementioned tall historical personalities to life. They have a difficult job, and while they may not all look exactly like the leaders they portray, they manage to convince us that they are the individuals they represent.

With his portrayal of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Sidhant Gupta, who made his debut as a young director in Vikramaditya Motwane’s Jubilee, adds yet another feather to his cap.

Even though he finds it difficult to comprehend the idea of splitting the subcontinent in two, the show portrays India’s first prime minister as a dapper lawyer who is completely comfortable in the rough and tumble of politics. The fact that Gupta, a thirty-something actor, is consistently convincing as Nehru in his late 50s, is no less than a marvel.

As Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Chawla excels in every way. He is portrayed as a tough guy who is ready to accept the idea of partition because he wants to prevent the seeds of religious mistrust and hatred from spreading throughout the nation.

The choice of Chirag Vohra to play Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is audacious. He wins over the audience after the wall of disbelief is broken, thus it works.

Arif Zakaria’s portrayal of a tubercular Mohammed Ali Jinnah is at the other extreme. The performer never fails to wow, even when the character lacks depth. Despite being the least conflicted of the key characters in Freedom at Midnight, Zakaria is able to instill important angularities in him.

Jinnah dismisses Fatima (Ira Dubey), his younger sister, as saying that regional identification is more powerful than religious identity, without allowing the argument to continue. Fatima is one of the few women in the cast who isn’t marginalised. He only moves in one direction, which deprives the representation of subtlety.

However, that isn’t the series’ worst flaw overall. Freedom at Midnight presents a composite of resonant, eternally relevant themes while choosing continuous involvement over mere enjoyment as it navigates the battlefield where the confrontation between different notions of nation and identity played out.

Without including the lessons to be learnt from the watersheds that shape nations, communities, and political formations, no historical play can be considered effective. The implications of actions made under duress and in response to roaring conflagrations are a recurring theme in Freedom at Midnight.

The series contains numerous insightful asides that serve as a commentary on the realities of our times, despite the fact that it portrays events that took place more than 75 years ago.

But even if one were to overlook these sharp realities about shedding the burden of foreign control, standing by one’s convictions in the face of serious provocations, and the conflict between duty and power, Freedom at Midnight has enough to keep the audience invested in the unfolding of the drama of a nation seeking to steady itself on dangerously slippery ground.

It tells a story full of known and unknown facts that are processed sensitively and skilfully, in addition to being brilliantly written and performed. It lacks the hectoring and screaming and grandstanding that characterise mainstream Bollywood.

The program honours history by painstakingly assembling the pieces that contributed to the creation of a vital and amazing, if unavoidably flawed, whole.